In global policy making, a huge issue that comes up with almost every discussion is the dichotomy between the geographical “North versus South,” or the “Developed versus the Developing” nations. Developed nations—such as the United States and countries incorporated into the European Union—are called upon by the developing world to contribute more resources and funding because they have been polluting more and for longer. This usually entails the developed nations to either start a multilateral fund, like the one imposed by the, or to be expected to change faster to set an example for the developing nations. However, when these nations take it upon themselves to “help” poorer countries by taking land rights away from the natives because the wealthier states feel that they are more knowledgeable of the treatment of said land, this is when we bring up the issue of land grabbing, or in conservational cases, “green grabbing.”

Land grabbing is the act of an organization, government, or other body of authority taking the land rights of a certain plot of land in an area outside of its normal territory or jurisdiction.1 Land grabbing is usually reserved for wealthy nations. This creates many issues because the land that the wealthier authority takes over is often within a developing and less wealthy nation which must forfeit their rights to the land, even if it has been a vital part of the nation’s culture for years. Private companies can also purchase land, and in these cases the purchase money goes to the local leader or government and cannot be guaranteed to go back to the natives that used the land.2 Land grabbing is usually used to extract natural resources or grow products that cannot be produced on the land of the wealthier nation. However, land grabbing can also be used to “protect” the land in which case it is typically referred to as “green grabbing.”

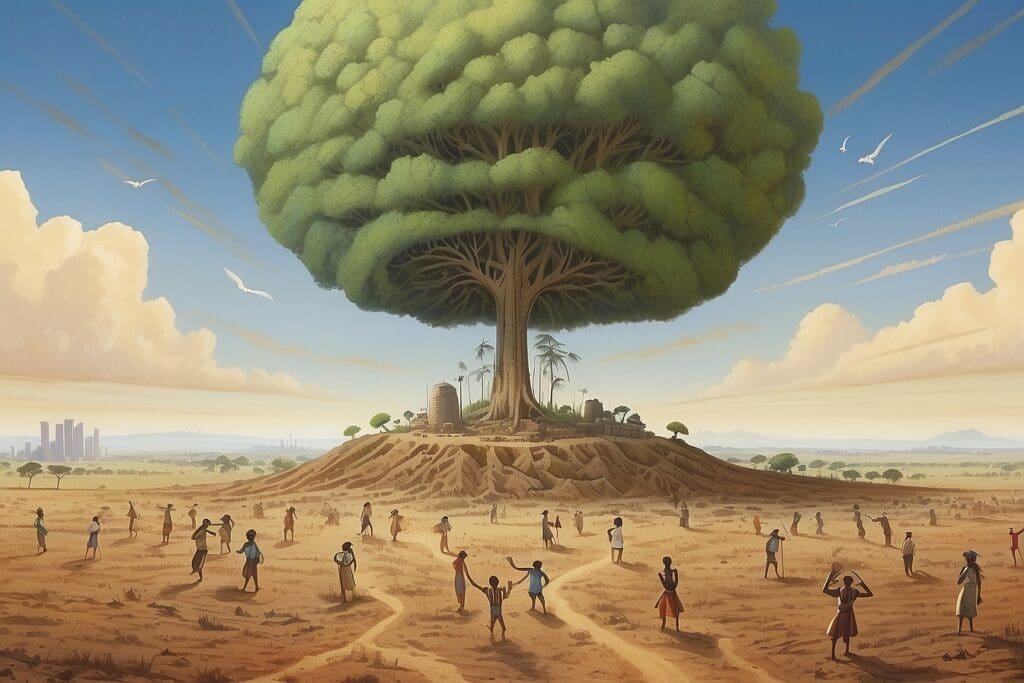

Green grabbing is the act of land grabbing to preserve or conserve nature. Green grabbing, or “eco-colonialism” can often be defined as: the appropriation of land and resources for environmental means, usually from economically challenged nations.3 This becomes an act that can be described as “pompous” or “conceited,” because the developed countries are essentially saying that they know better than the people that live there, even when it comes to how to protect and what to do with their own land. This takes away from the local people the right to use the land as well as the resources it provides. Instead of allowing the land to be used as the natives decide, a monetary value is given to the nature and land based on how it can be used as for example, a source of ecotourism ![]() and other environmental purposes.4 Furthermore, since most of this land is taken for agricultural reasons, this is not only an issue of land rights but also of food scarcity. The land that is taken by non-governmental organizations, private companies, and foreign governments originally belonged to the locals, usually for purposes of growing food and grazing for their livestock. By taking these lands away, crops and other things produced that had been used to nourish the people of the land is instead exported or is not produced at all.5

and other environmental purposes.4 Furthermore, since most of this land is taken for agricultural reasons, this is not only an issue of land rights but also of food scarcity. The land that is taken by non-governmental organizations, private companies, and foreign governments originally belonged to the locals, usually for purposes of growing food and grazing for their livestock. By taking these lands away, crops and other things produced that had been used to nourish the people of the land is instead exported or is not produced at all.5

Unfortunately, in some instances green grabbing has been corrupted and used as a way of profiting from the existence of nature. For example, in Guatemala, the Guatemalan Maya Biosphere Reserve7 has been taken from the natives by the Wildlife Conservation Society as well as many other ecotourism companies and conservation agencies and has been set aside as land used for a “Maya-themed vacationland,” which is even protected by the military.8 Another purpose for green grabbing is to put in place a stocks are not tampered with. The problem with this is that the forests are not vast lands of carbon stocks to the local people. To the locals, it is just a way of life and the forest and land around them play a huge role in everything they do. To take it away completely changes their lifestyles and may throw them deeper into poverty and starvation.9 Land grabbing is particularly a problem in Africa because many African nations are undeveloped. However, as stated before, land grabbing can cause more problems than solutions. A case of green grabbing in Africa can be seen in the nation of Chad. In the 1990’s, protected land increased from 1 to 9.1 percent, displacing about 600,000 people. As a hot spot for refugees from surrounding countries fleeing civil warfare, Chad has many people other than just its own citizens to find new homes for due to “green grabbing,” estimated to be re-homing almost 7% of its inhabitants.10

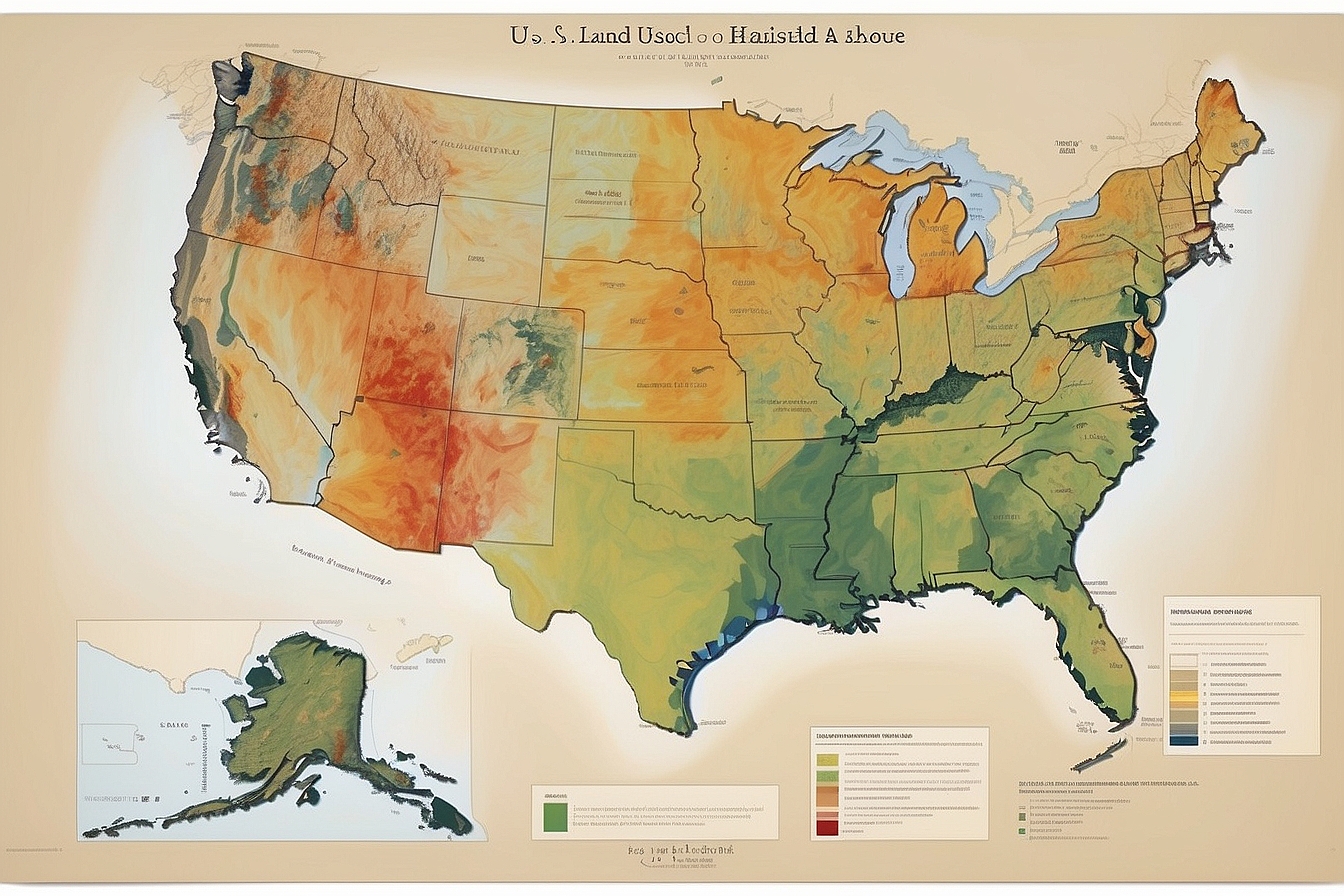

Although land grabbing—green grabbing in particular—entail international efforts to conserve resources and nature, it has become a way for wealthier nations to make up for their negative effects on the environment by taking it upon themselves to “help” other nations. However, this has left many of these already poor countries in worse states. When a nation has little global economic power, all they have is their land and their resources. Taking these away leaves them with almost no means of survival. International assistance is needed for these developing nations, but taking away their land rights and resources is not the way to do it. Taking away from them to make up for what developed countries have done is injustice not just for these nations, but also to the rest of the planet. Conferences like Rio +20 are set up to discuss what to do in order to save our ailing environment, but green grabbing does not seem to be slowing down even with its many critics. How will this problem be solved if the people who are largely affected do not have a large voice in the international decision making community? Their voices need to be heard, because the land that wealthier nations see as a commodity is not something you can slap a price on – it is their way of life and what they prize the most. Before a nation grabs land from another nation, it should look into the way it is allocating its own resources because controlling more land while losing control of your own will ultimately leave a worse mark on the environment.