Waste to Energy Incinerators? Every year, our world produces thousands of tons of garbage. The United States alone generates over 230 million tons of trash, equally about 4.6 pounds per person in a single day.1 Only a small percentage of that garbage is recycled and the rest of it is incinerated or piled into landfills. But as landfills across the world are closing annually due to over-capacity or environmental degradation, the remaining garbage is left without a home. So what is the alternative? Many communities would argue that a commitment to “zero waste” is necessary to solve the garbage problem but others have found another solution: waste to energy incinerators.

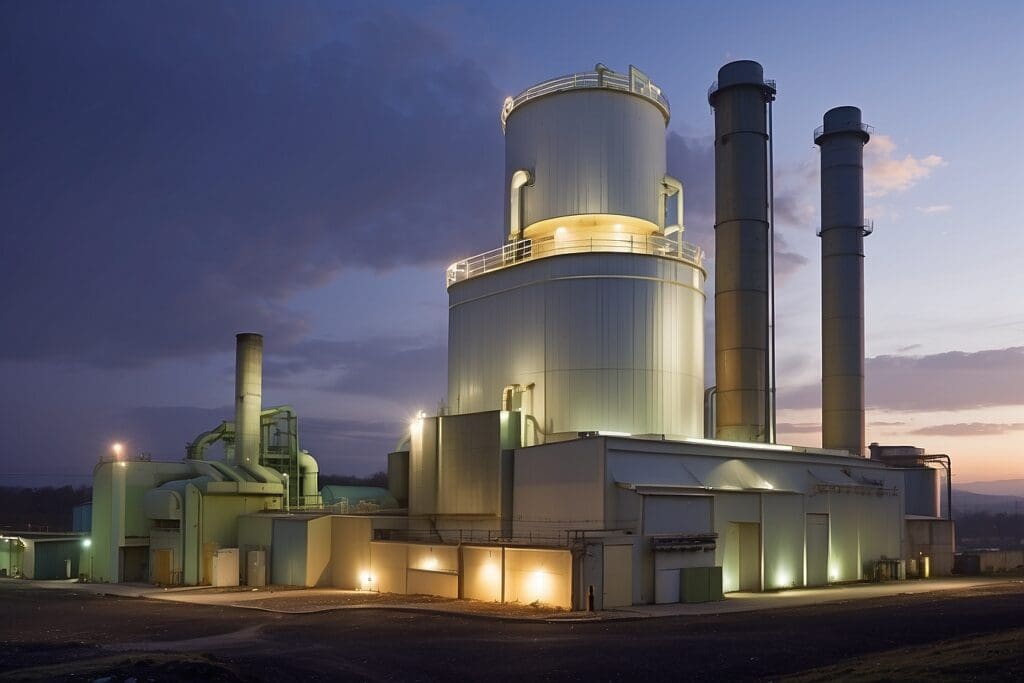

The incineration of garbage has been around for over a century as a waste treatment technology. The process simply takes garbage that would normally be dumped in a landfill and burns it, reducing its volume by up to 96 percent. Many densely populated countries with little space for landfills, like Japan, France, and Germany, rely heavily on incineration as a waste treatment method. However, historically this burning process creates other problems like pollution, a release of other toxins, and undesirable odor. Therefore, parts of Europe and in particular Denmark, have found a much cleaner alternative in the waste to energy incinerator. According to an article in the New York Times, “this new type of plant converts local trash into heat and electricity. Dozens of filters catch pollutants, from mercury to dioxin, that would have emerged from its smokestack only a decade ago.”2

Waste to energy incinerators also reduce the cost of energy for the communities they supply, reduce their reliance on oil and gas as an energy source, reduce the amount of garbage sent to landfills, and reduce the amount of carbon dioxide emissions in the atmosphere. Denmark currently “has 29 such plants, serving 98 municipalities in a country of 5.5 million people, and 10 more are planned or under construction. Across Europe, there are about 400 plants, with Denmark, Germany and the Netherlands leading the pack in expanding them and building new ones.”3 Conversely, only 10 percent of garbage is sent to these incinerators in the United States. And according to the Integrated Waste Services Association, “as of 2008, America’s solid waste industry operated 87 waste-to-energy facilities that generated more than 2,700 megawatts of electricity, enough to power 1.7 million homes.”4

Why is the United States so slow to embrace the waste to energy incinerators as a renewable energy resource? It could easily be argued that the issue of space alone is enough to prevent the U.S. from moving to waste to energy incinerators. Countries like Denmark and Germany simply do not have the same amount of land available to create more or larger landfills as the United States so it provides them with a necessary incentive. From an environmental standpoint, however, waste to energy incinerators should outweigh the option of landfills as a waste management option but some environmentalists tend to disagree. In the U.S., as individual states and municipalities decide the fate of their own waste, many state officials and environmental organizations believe that these new incinerators could potentially destroy their overall goal of zero waste within communities. Trash has more economic value and a lighter impact on climate change when reused, recycled or composted than when incinerated or placed in a landfill.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) says, “[r]educing the need for new materials should be the top priority, followed by reuse, recycling, waste-to-energy incineration, and placement in a landfill.”5 Therefore, many waste to incinerator opponents believe that if resources are spent on new incinerators, these plants will be competing with the same resources as the already existing recycling and composting centers. The waste to energy incinerators are believed to essentially just put a band-aid over the trash problem and that a zero waste or an emphasis on recycling and composting is a better long-term approach to our world’s garbage problem.

In the end, an environmental victory in one country may always be regarded as a step back elsewhere. In Horsholm, Denmark where waste to energy incinerators are a major energy source and landfill space is over capacity, only 4 percent of its waste goes to landfills, 61 percent of it is recycled, and 34 percent of it is sent to the incinerator.6 Will that ever be a reality in a country like the United States, which has yet to reach its landfill capacity? The answer may not be known until it becomes necessary but in the meantime, it will be important to work towards zero waste.