A reservoir is considered to be a “dead pool” when the water level behind a dam is too low to spill water or generate climate change and water mismanagement.1 This apocalyptic prediction has become even scarier over the last few years as the Southwestern United States2 has experienced a period of extended drought.3 But how can we be sure that James Lawrence Powell is correct? Will the Southwest really run out of water in less than a decade?

The Colorado River Dams

Around 30 million Americans from Colorado, Arizona, Nevada, California, Utah, Wyoming and New Mexico depend on the Colorado River as the main source of their drinking water.4 Historically the Colorado flowed all the way from the Rocky Mountains to the Gulf of California. Before engineering projects were initiated in the 1900s, the Colorado was “a river of extremes like no other in the United States.”5 The river discharge rate could fluctuate from peaks of more than 100,000 cubic feet per second (2,800 m3/s) in the summer, to lows of less than 2,500 cubic feet per second (71 m3/s) in the winter.6 To help make the water supply more dependable and generate more than 12 billion kWh of electricity a year for a growing population in the southwest, large dams like the Hoover Dam and Glen Canyon dam were built across the river.7

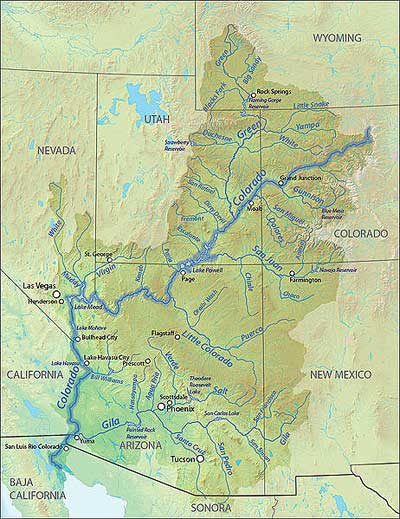

Map of the Colorado River Basin.8

The dams built along the Colorado were meant to store up to four years’ supply of water for the Southwest, but lately the reservoirs have been at less than 60% capacity.9 The dropping water levels are attributable to a variety of different factors. Most importantly, the water from the Colorado is overprescribed.

The Colorado River Compact was signed in 1922 after the completion of the Glen Canyon Dam, which created Lake Powell. According to this compact, the upper Colorado River basin states are required to deliver 75 million acre feet (“An acre-foot is roughly the amount of water used by a family of four in a year”10) to the lower basin over a ten-year rolling average. In 1944, a treaty with Mexico pushed the required delivery up to 82.3 million acre feet every year to ensure that Mexico gets enough water.11 Unfortunately, the Colorado River Compact appears to have been made in an exceptionally wet year.12 More water leaves the Colorado than it can supply in an average year. What’s worse is that due to climate change there hasn’t been an “average” year in over eleven years.13 2012 was one of the driest years on record, with August and September of 2012 being the two months with two lowest inflows in the history of Lake Powell. Lake Mead is also in major trouble after dropping to its lowest level in 2012 since the Lake was created 75 years ago. If the Lake drops another seven feet, it will trigger water shortages throughout the lower river basin states.14

In addition to falling water levels, salinity has also become a problem in the Colorado River. Salinity levels have increased over the last several decades to almost 9 million tons of salts annually as water evaporates from reservoir surfaces, salts run off of soils and rocks, and farm irrigation increases the amount of salt in the soil. Indeed, the concentration of salt in the lower reaches of the Colorado makes the water undrinkable without utilizing desalinization plants.15 In a similar vein, salinity is also a problem that we are fighting to address in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, which provides fresh drinking water to 23 million Californians.

The Future of the Colorado River

If the Southwestern United States continues to warm, it appears that James Lawrence Powell’s predictions in Dead Pool may actually be correct. In order to avert such a crisis, western states will have to act fast. States are already encouraging people to xeriscape their lawns, use reclaimed water, build rain barrels, and take shorter showers. Both the cities of Phoenix and Las Vegas run large conservation programs: “between 2000 and 2009, Phoenix’s average per-capita daily household [water] use has dropped almost 20 percent; Las Vegas’s has dropped 21.3 percent.”16 Meanwhile, some water managers are calling for more drastic measures, such as enormous pipeline projects to divert water from the Mississippi River.17 Let’s hope that the West’s excessive water use doesn’t turn the Mississippi into a dead pool as well.

Lake Powell, 1999

Lake Powell, 2003

Lake Powell, 2005

Lake Powell, 201018