It seems that the enormity and mysteriousness of the world’s oceans have led us to believe that their resources are inexhaustible. However, according to some estimates, the commercialization of fishing practices (starting about 50 years ago) has reduced the populations of large commercial fish, such as bluefin tuna and cod, by 90 percent!1 Due to popularity among sushi chefs, bluefin tuna (also known as hon maguro or toro) are being caught faster than they can reproduce. A particularly delectable and iconic fish, the bluefin is a good fish to examine more closely in order to understand the destruction wrought by overfishing around the world today.

Bluefin Tuna

The Atlantic Bluefin tuna is one of the world’s most beautiful fish. Called “Bluefin” because of their coloring—metallic blue on top and silver-white on the bottom—the fish are camouflaged from both above and below. The majesty of the bluefin lies not only in its gorgeous coloring, but also in its behemoth size and speed. These carnivores grow to an average size of 6.5 feet and 550 pounds, and much larger fish are not uncommon. Due to their speed (up to 43 miles per hour) and size, bluefin are able to migrate vast distances every year. In addition, because Bluefin are warm-blooded, they can survive in cold and warm waters from Newfoundland to the Gulf of Mexico.2

3

3

The incredible range and delicious belly meat of the tuna has made it a popular fish for centuries. In the 1970s, demand and prices for large bluefins soared worldwide due to new fishing technologies. As a result, bluefin stocks, especially of large, breeding-age fish (the fish mature and reproduce at the ripe old age of 8),4 have decreased dramatically, some believe to the brink of extinction.5

Global Market for Bluefin

Global fishing capacity could reel in the world catch (all of the fish in the world) four times over. And much of that fishing might is aimed at the Bluefin. In fact just one bluefin tuna sold in 2009 at an auction in Tokyo for more than $100,000! The incentives to catch bluefins are incredible. Pound for pound, Bluefin is the most expensive and sought after fish meat on the planet.6

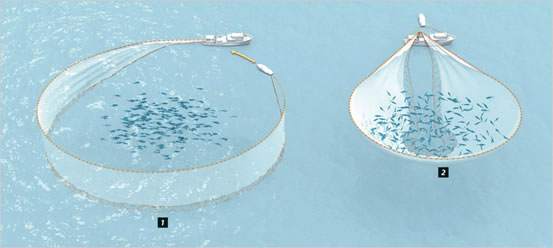

Bluefin tuna can be caught in a number of different ways, including with purse seines and longlines. Longlines—lines that have hooks attached to them at fixed intervals—are very common for catching tuna. Unfortunately, this method results in large bycatch, which are other species that get caught in the process of capturing the tuna, and these species are often threatened or endangered species such as sea turtles, sharks and seabirds.7 As of now, there are no international laws to reduce bycatch.8

Quantifying the effect of bluefin overfishing is a daunting task. As one researcher remarked in the documentary The End of The Line, “counting fish in the ocean is just is easy as counting trees, except they’re invisible and they move.”9 The International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) believes that Western Atlantic bluefin tuna have been reduced by at least 82 percent over the last few decades. Moreover, ICCAT estimates that as few as 25,000 individual mature bluefin tuna remain.10

Tuna Ranching

Some hail bluefin tuna ranching as the solution to the declining fish problem. In fish ranching, small bluefin tuna are brought from the wild and fattened in open net pens. However, many environmentalists argue that because the bluefin tuna populations are so depleted, taking young bluefin out of the ocean will only exacerbate the problem.11 In addition, large quantities of other fish must be used to feed these tuna. This leads to a concern that ranching practices may lead to decimation further down the food chain.

So what is to be done about overfishing?

Numerous nations, including the U.S. and Japan, participate in international management bodies that work to maintain global tuna populations. Fishing is supposed to be controlled by the internationally agreed quotas, which is the amount fishermen are allowed to catch. Unfortunately, these programs are proving ineffective.

First, there is the issue of setting proper quotas. Most recently, scientists have recommended that the bluefin catch worldwide be limited to 15,000 tons. This is a bare minimum recommendation, aimed to just barely avoid collapse of the fishing stock. In order to rebuild the population, the catch quota would have to be closer to 10,000 tons. At a 2010 meeting, world leaders with ICCAT voted to set the quota at 29,500 tons—twice what it should be to avoid collapse.12

Second, there are issues with enforcement. In the Mediterranean, giant factory ships (mostly from European nations such as France, Italy, and Spain) are using purse seiners to scoop up entire schools of bluefin in order to fatten the tuna before they sell them to Japan.13 Ships in the Mediterranean often ignore quotas. Official figures show that these ships catch around 61,000 tons of tuna a year. That’s one third of the total Bluefin tuna population!14

Nets, known as purse seiners, used to catch tuna.15

Right now, the best way to help protect the bluefin tuna is to support quotas and stop eating the bluefin!16 If you eat fish on a regular basis, consider how your eating habits may be putting species at risk. To learn more about sustainable seafood habits, check out this guide: Sustainable Seafood Guide.