When you think about saving the environment, what comes to mind? Perhaps you think about stopping deforestation, reducing pollution and harmful emissions, promoting biodiversity, or protecting the Earth’s waters—but how many times have you stopped and thought about soil erosion? According to David Pimentel, professor of ecology at Cornell, “Soil erosion is second only to population growth as the biggest environmental problem the world faces.”1 Even though soil erosion is an environmental threat that grows in severity each year, it does not receive the attention it deserves, mostly because, as Pimentel puts it, “who gets excited about dirt?” So let’s focus on the dirt!

Types of Soil Erosion

For the most part, erosion—which is the process of weathering and transport of sediment, soil, rock and other particles in the natural environment—is caused by two main catalysts: 1) wind, and 2) water.2 These natural causes of degradation can come in many forms and affect a full spectrum of natural environments. Runoff from irrigation practices or precipitation can carry loose topsoil down a slope and deposit it into streams and rivers, many miles from its source. Canals and even gorges can also form from erosion, so what may start as a small stream can carve away at the soil until you are left with a network of gullies (for an extreme version, think Grand Canyon). This “gully erosion” is highly visible, affects soil productivity, restricts land use, and can threaten roads, infrastructure, and buildings.3

“Gully Erosion” 4

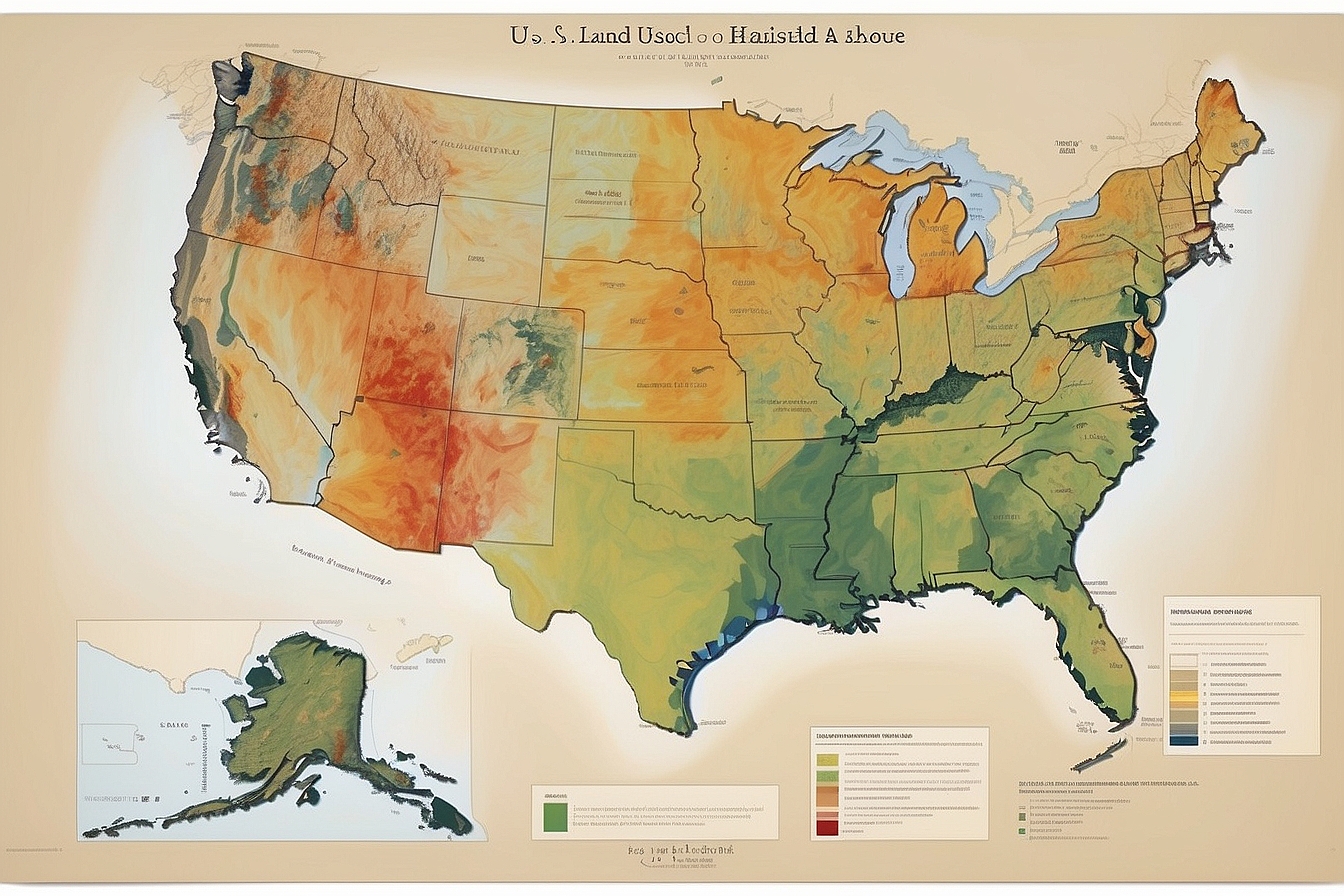

Wind Erosion—In arid regions, such as plains used for agriculture or grazing, the greatest cause of erosion is often wind. If land is left fallow or becomes over-grazed, the wind can remove topsoil and decrease soil fertility or even lead to “scalding.” “Scalding” occurs when most plants die from lack of nutrients or water, and the soil becomes very hard and smooth. As a result, “most of the rainfall is lost via runoff or from moisture evaporated from ponded water, leaving little moisture for crop or pasture growth in an environment where rainfall is already a limiting resource.”5 If you want an extreme example of these sorts of conditions, think Dust Bowl. This period of enormous dust storms in the American Midwest during the 1930s was caused by poor farming practices, drought, and erosion.6 “The soil, depleted of moisture, was lifted by the wind into great clouds of dust and sand which were so thick they concealed the sun for several days at a time. They were referred to as ‘black blizzards.’”7Agricultural practices were altered after this catastrophic, decade-long event, but many argue sufficient preventative measures are still not in place to address erosion concerns. Soil is being lost around the world at alarming rates, and if action is not taken, it could have dire effects on food systems and national economies.

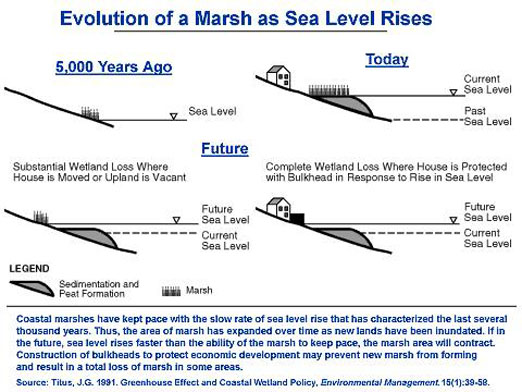

Water Erosion—Another major type of erosion is shoreline erosion. This occurs when large storms change the shape of beaches and dunes, or cause the beaches and dunes to “migrate” due to high-water levels and strong waves. Man-made structures that are created in response to rising sea levels (such as sea walls) are also responsible for altered beach ecosystems. The consequences include loss of wetlands, loss of beach habitat, and in extreme cases, loss of entire beaches.8

With the exacerbating effects of climate change upon rising sea levels and storm frequency and intensity, it is likely that beach erosion and migration will continue to be a problem for coastal regions going forward.9 The EPA estimates that between 80 and 90 percent of the sandy beaches along America’s coastlines have been eroding for decades.10 “In many of these cases, individual beaches may be losing only a few inches per year, but in some cases the problem is much worse… some beaches lose 50 feet of beach every year.”11 This is not even taking into account the eroding, or collapsing, of costal cliffs—a phenomenon becoming all too common on the west coast. These types of land movements can destroy entire housing developments.

12

12

Soil Erosion and Our Environment

As Professor Pimentel explained in a 2006 University of Cornell study, “erosion is one of those problems that nickels and dimes you to death.”13 For an example: if a rainstorm removes 2/5 of an inch of soil, over 2.5 acres of land, it would take natural processes 20 years to replace the 13 tons of topsoil that were lost.14 Furthermore, the eroded soil is often topsoil, which has the greatest concentration of organic matter and microorganisms and is where most of the Earth’s biological soil activity occurs. Plants concentrate their roots in and obtain the majority of their nutrients from topsoil.15 So we can see that large amounts of soil erosion is extremely problematic, especially given that 99.7% of human food comes from cropland.16 Pimentel’s study found losses of more than 37,000 square miles of cropland per year due to soil erosion. With more than 3.7 billion people already malnourished worldwide, addressing this issue should be a top priority. 17

The United States is losing soil at a rate 10 times faster than the soil replenishment rate—while China and India are losing soil 30 to 40 times faster.18 Economic losses resulting from the decreased soil productivity in the United States alone are $37.6 billion per year.19 Increased erosion means decreased water storage in soil, decreased biodiversity, losses of nutrients and organic matter, and an increase in agricultural pollutants and fertilizers in waterways.20

Aerial photo of erosion on farmland in Montana 21

If the situation wasn’t bad enough already, a growing body of evidence supports the conclusion that climate change increases erosion rates. 22;23 Intense weather extremes such as heavy rain, longer droughts, or more intense heat spells, worsen erosion in agricultural regions.24 These conditions can also shift the growing season, thus decreasing crop yields and forcing later planting dates for crops like corn, which also increases soil loss.25

What Can We Do?

Professor Pimentel claims that taking certain “simple” measures could drastically change the levels of erosion that take place around the world.26 One of the most important things is keeping the land “covered,” which means keeping the land growing some sort of agriculture. Barren land can deteriorate quickly and become unrecoverable in the short-term. If global agriculture practices focused on using cover crops whenever the land is not being used for food crops, then we would see benefits in the forms of reduced erosion, higher water content in the soil, and increased nutrient levels which promote future biodiversity. Pimentel also points out that we need to reduce the need for developing countries to clear their forests for agriculture and grazing—deforestation —an issue which many groups are attempting to address around the world.27 Erosion gradually degrades our lands while further threatening an already fragile food system. However, if we increase awareness and work to combat this steadily increasing global threat through improved agricultural practices, we can likely get our soils back on track, and reduce erosion rates to naturally replenishable levels.