By the year 2050 the world population is estimated to be over 9 billion.1 Over the course of their lifetimes, each of these people will require a few essentials such as food, shelter, and utilities. To accommodate these needs academics and industry leaders are debating whether or not we should divert farmland or crops to biofuel production. Biofuels are produced from living organisms. By definition, 80% of their composition must come from renewable materials rather than fossil fuels.2 This sounds like a good thing for the climate, but all of that organic matter must be grown somewhere. Some critics of biofuels are worried that growing crops like corn, sugarcane, and vegetable oil for fuel may result in food shortages and increased global hunger.

3

3

Biofuels

The history of biofuels is longer than you might expect. In the mid 1800s, camphene—made from vegetable oil—was a more popular choice than both whale oil and gasoline-based kerosene for lamps.4 In fact, Henry Ford first designed his classic Model-T Ford to run on corn oil and peanut oil.5 However, by the mid-20th century fossil fuels had become the dominant source of liquid fuel. The discovery of large reserves of oil throughout the world allowed gasoline to dominate the market until the oil embargo of the 1970s.6

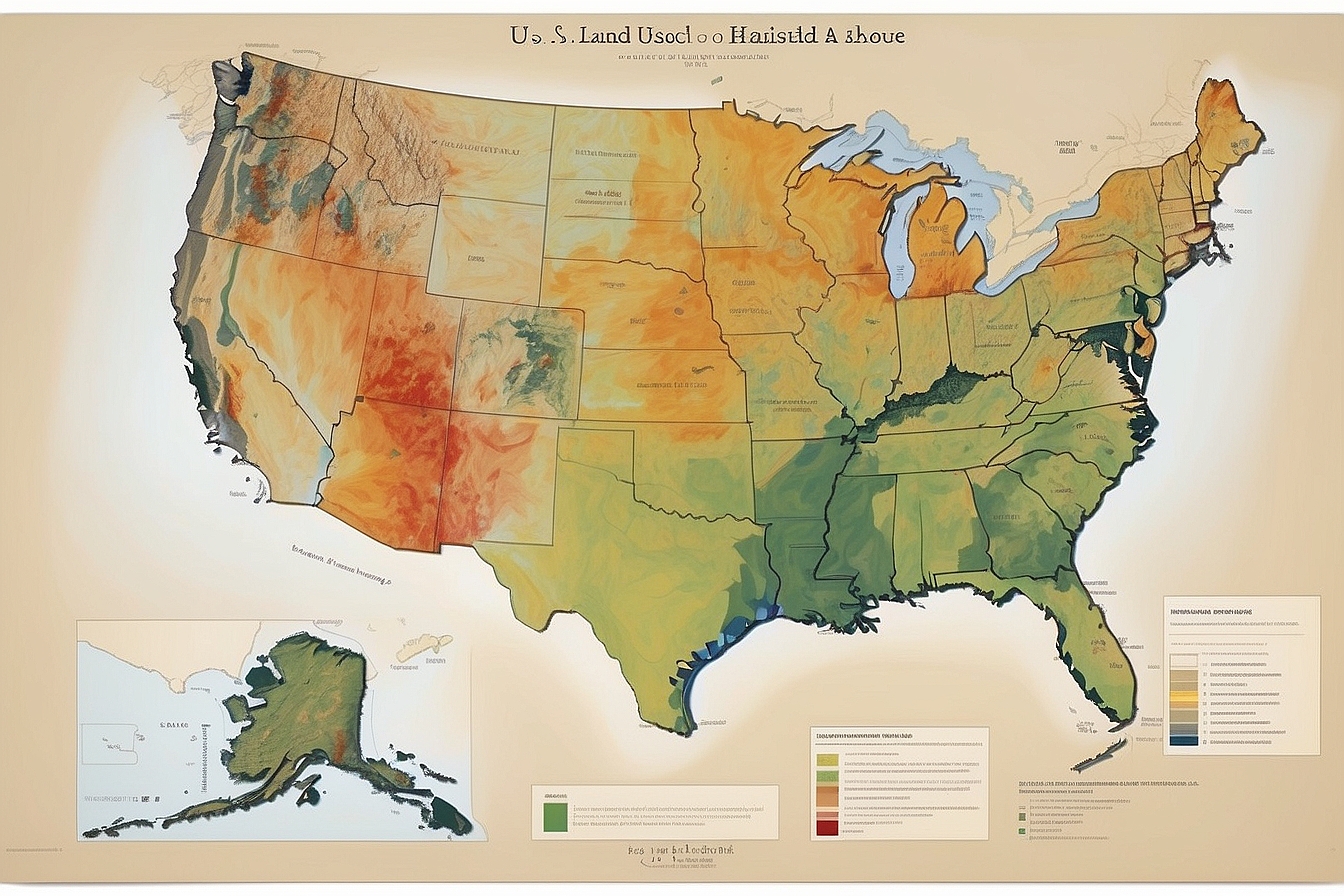

In the 1990s demand for biofuels started to grow as people became concerned about the United States’ dependence on foreign oil and the role of burning fossil fuels in biodiesel by 2012.7 Furthermore, the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007 required that 9 billion gallons of renewable fuels be added into the fuel supply by 2008 and 36 billion gallons be added by 2022.8 These and other policies have led to meaningful changes in our country’s fuel supply. As of 2008, ethanol production was 900,000 barrels per day, and ethanol made up over 10% of the gasoline mix in U.S. fuel.9 In 2012, ethanol remained at 10% of the gasoline mix—labeled as E10—throughout most regions of the U.S. In the Midwestern states E15 is more often found, as gasoline mix with 15% ethanol, and can only be used by light-duty vehicles from model years 2001 and beyond. Only “flex-fuel” vehicles can use gasoline with more than 15% ethanol.10

What’s Wrong With Biofuels?

carbon dioxide polluters while plants are renewable resources that actually help take carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere.11 Unfortunately, the reality of biofuels is not so rosy. To begin with, the process of growing crops, particularly in our industrialized food system, is highly energy intensive. Creating biofuel is an energy-intensive process: we have to use machines to plant the crops, make fertilizers and pesticides, harvest the crops, and actually process the plants into fuel. It takes such a great amount of energy that many wonder whether ethanol from corn actually provides more energy than is required to grow and process it.12

While the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007 put a cap on the amount of corn that can be allocated for fuel at 15 billion gallons “so as not to overly interfere with the food supply,”13 lately this 15 billion gallon cap has amounted to 40% of the country’s corn crop. As one critic from the Environmental Working Group put it: “It’s unfathomable that the corn ethanol industry can continue to assert that using 40 percent of the corn crop has no impact on food stocks or commodity prices.”14

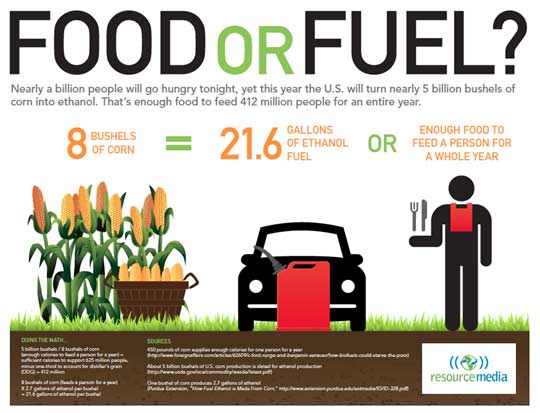

These critiques of ethanol are flawed in some respects. There is no guarantee that had the 40% of corn crop grown as ethanol been grown as food instead it would have all survived to be edible or that it would all have been used to feed humans rather than liveestock.15 Additionally, the critique ignores the benefit that ethanol production produces by creating a co-product worth forty million tons of livestock feed that is cheaper than corn.16 However, as food commodity prices increased over the last year due to an extended drought , the outcry has become louder. One commonly shared infographic simplifies the debate by claiming that the corn harvested for biofuel production in 2012 could have fed 412 million people for a year:17

18

18

Rethinking the Food vs. Fuel Debate

It has been frustrating for me to research the heated “food versus fuel” debates, because so many people use heated rhetoric and talk in very broad terms. To me it seems much more productive to approach the question on a more local level. For example, does the region already have more than enough food to feed its population? Do people living around the area support endangered species living there? What’s the soil type and the annual rainfall? It seems like once biofuel production is approached on a local level, farmers can identify which crop or group of plants are the best match for the local landscape, and they can brainstorm ways to creatively utilize surplus land to benefit not just energy production, but the environment as well. For example, biofuel crops could be planted along the edges of farmers’ fields to make use of wasted space and alleviate run-off. Rather than switch monoculture corn food crops for monoculture corn fuel crops, mosaics of corn crops could be planted to create better habitats for wildlife than the typical crop monocultures.19

It seems like the debate has gotten too bogged down in an “either /or” dichotomy. The decision to convert a plot of land to biofuel crop production should depend on individual tradeoffs between food availability, other alternative energy options, the environmental friendliness of an energy crop design, and the project’s economic viability. There should be the opportunity to research other types of biofuel besides ethanol. And there should be an open discussion about the real costs and benefits of different options, taking a serious look at industry subsidies and how those might influence the food and fuel industries.