Soot is made up of microscopic particles that are released from burning fossil fuels at different sources like power plants , smokestacks, diesel trucks, and wood-burning stoves. The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recently released new soot regulations as its first major promulgation since the November 2012 Presidential election.

1

1

History of Soot Regulation

Soot in the atmosphere causes several environmental problems, such as haze and the acid rain . This pollution degrades water quality by making our waterways more acidic, depletes the nutrients in the soil, changes the nutrient balance in natural ecosystems, and erodes iconic stone monuments and buildings.

Even the Arctic is suffering from the world’s high soot levels. Surveyers of Arctic glaciers have documented that soot, also known as black carbon, is a significant contributor to rising sea levels which are a major threat to the Arctic and survival of its wildlife and ecosystems.

Not only does soot cause hazy skies and climate change, breathing it in can also lead to lung and heart problems, including heart attacks, strokes and asthma attacks. Soot poses a threat to public health primarily because of its small size. Particulate matter is so small that it can easily enter a person’s lungs and bloodstream: “Microscopic particles can penetrate deep into the lungs and have been linked to a wide range of serious health effects, including premature death, heart attacks, and strokes, as well as acute bronchitis and aggravated asthma among children.”3 The American Lung Association also indicates that breathing particle pollution may cause “cancer and developmental and reproductive harm.”4

In order to protect the public from soot and other particulate matter, the Clean Air Act requires the EPA to review air quality standards every five years and update them as needed. The agency updated the national limit for the 24-hour fine particle (PM2.5) standard from the 1997 level of 65 micrograms per cubic meter (µg/m3) to 35µg/m—a micrometer is 1/1000th of a millimeter and there are 25,400 micrometers in an inch! However, the EPA didn’t strengthen the standard for soot 2.5 micrometers in diameter or less.5 Such fine particles are even smaller than dust and mold particles, and are approximately 1/30 of the size of a human hair.

The American Lung Association’s 2012 State of the Air Study found that nearly 6 million people in the U.S. live in an area with unhealthy year-round levels of particle pollution. Given these numbers and the fact that the EPA had not updated its soot emissions standards in over a decade, a coalition of States and Earthjustice7 —on behalf of the American Lung Association and the National Parks Conservation Association—sued the EPA. These groups argued that the Bush administration had ignored science and its own experts when it decided in 2006 not to lower the nearly decade-old annual standard for soot. Although the EPA initially promised it would review recent science and issue a decision in 2011, the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia had to force the issue. The Court told the EPA it had to issue new standards by June 2012 to “protect public health and comply with the Clean Air Act.”8

New Soot Regulation

The new soot regulation issued in December 2012 mandates that the current 15 μg/m3 (micrograms per cubic meter of air) be reduced to between 12 and 13 μg/m3, starting in the year 2020, which is a reduction of up to 20 percent.9 Following the announcement of the new regulations clean air advocates and industry representatives alike voiced their opinions.

Opponents of the new standard warned that it will make it harder and more expensive for businesses to expand or build new electricity plants, and that it will add to the jobless rate. Ross Eisenberg, vice president of the National Association of Manufacturers says he fears that the rule is the beginning of a “regulatory cliff” that includes a forthcoming EPA rule on ozone, or smog, as well as pending greenhouse gas regulations for refineries and rules curbing mercury emissions at power plants.

In contrast, many democrats and nonprofit leaders applauded the standards. A letter signed by fifty-six House Democrats said “morally and fiscally, [the new standards are] a no-brainer.”10 The letter cited a 2011 report issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which indicated that racial minorities are more likely to live in areas where air pollution fails to meet national standards.11

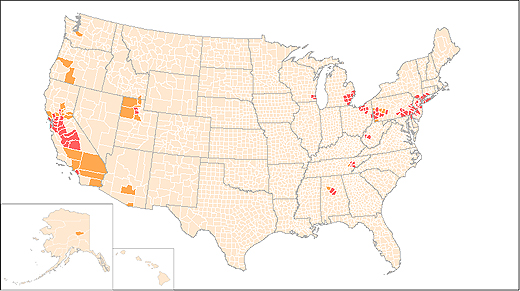

EPA chief Lisa Jackson and other Agency officials said the new rule was based on a rigorous scientific review, and that the EPA’s financial analysis refutes opponents’ claims that the regulation will have negative economic effects. Currently, only sixty-six U.S. counties are out of compliance with the existing air-quality rules on soot. The agency projects that, with the exception of seven counties in California that have persistent air-quality problems, all U.S. communities should be able to comply with the new limits by 2020. Ninety-nine percent of U.S. counties are projected to attain the new standard without taking any additional action.12

Map of 24-hour fine particle nonattainment counties—counties in red are fully out of attainment levels and counties in yellow are only partially out of attainment. 13

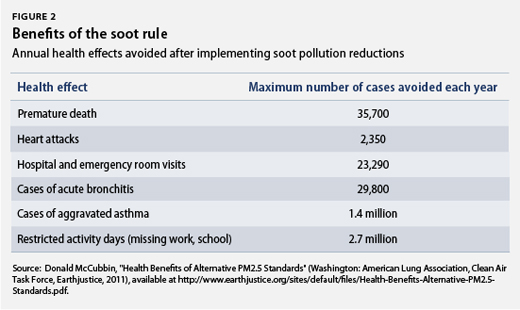

The tougher standard should actually create a net economic benefit. The cost of implementation is expected to range between $53 million and $350 million.14 Meanwhile, the health benefits of the standard are estimated to be anywhere from $4 billion to $9 billion annually due to fewer hospitalizations and lost workdays, along with other benefits.15 The EPA estimates that by 2030 the new standards should “prevent up to 40,000 premature deaths, 32,000 hospital admissions and 4.7 million days of work lost due to illness.”16 This means that every dollar invested in cleaning up soot pollution will yield up to $86 in health benefits!

This table demonstrates the breakdown of health benefits expected from the new rule ☺

17

17