Stinking, stagnant waters filled with mosquitoes and other bugs… oozing muck… Although wetlands don’t seem like the most appealing places to visit, they are a crucial part of the ecological chain. Wetlands provide resting places for birds, habitats for an astounding variety of species, transform runoff water from an environmental hazard to a productive part of the ecosystem, and help to protect clean water.

What is a Wetland?

The simplest definition of a wetland is that it is an area where water covers the soil, or is at or near the surface of the soil for all or most of the year. For regulatory purposes under the United States’ Clean Water Act, the term wetlands means:

those areas that are inundated or saturated by surface or groundwater at a frequency and duration sufficient to support, and that under normal circumstances do support, a prevalence of vegetation typically adapted for life in saturated soil conditions. Wetlands generally include swamps, marshes, bogs and similar areas.1

The amount of water in the soil (the hydrology) of a wetland is the main determinant of the types of plant and animal communities that will live in a particular wetland. Wetlands vary from region to region due to these differences in soils, topography, climate, hydrology, water chemistry, vegetation, and other factors, including human disturbance. In fact, wetlands are found on every continent of the globe, from the tundra to the tropics, except for Antarctica.

2

2

Main Types of Wetlands

The two main categories of wetlands are: 1) coastal, often referred to as tidal wetlands, and 2) inland, often referred to as non-tidal wetlands.

Tidal Wetlands: In the U.S., tidal wetlands are found along the Atlantic, Pacific, Alaskan, and Gulf coasts, where seawater mixes with fresh water. Due to the harsh conditions created by salty water and tidal fluxes, many shallow coastal areas are unvegetated. Some plants, including certain grasses, have nonetheless successfully adapted to this saline environment to help create coastal wetland areas. Mangrove swamps, with salt-loving shrubs or trees, are the most common wetlands in tropical climates such as in southern Florida and Puerto Rico.

Non-Tidal Wetlands: Wetlands that are not along the coast are most common on river floodplains (riparian wetlands), in depressions surrounded by dry land (playas, basins, and “potholes”), along the edge of lakes, and in other low-lying areas where there is a good amount of precipitation or the groundwater reaches the soil surface (vernal pools and bogs). Inland wetlands are fairly diverse, due to the varying amounts of rain they receive, and may include marshes and wet meadows dominated by “herbaceous plants, swamps dominated by shrubs, and wooded swamps dominated by trees.”3

Certain types of wetlands are common to particular regions of the United States:

- Northeastern states, north-central states and Alaska: bogs and fens;

- Midwest: wet meadows and wet prairies;

- Arid and semiarid West: inland saline and alkaline marshes and riparian wetlands;

- Iowa, Minnesota and the Dakotas: prairie potholes;

- West: alpine meadows;

- Southwest and Great Plains: playa lakes;

- South: bottomland hardwood swamps;

- Southeast coastal states: pocosins and Carolina Bays;

- Alaska: tundra wetlands.4

Why Are Wetlands Important? Wetlands are important for a variety of reasons, including:

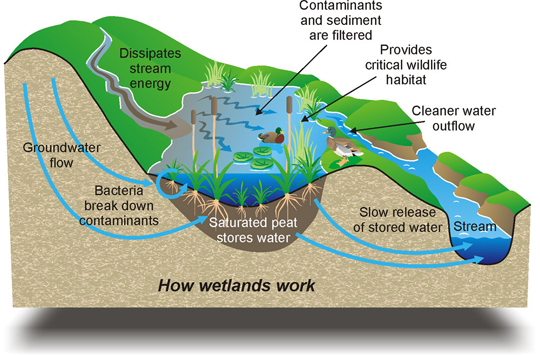

- Flood and Storm Water Control: Wetlands absorb and slow down the movement of rain and melt water, minimizing and stabilizing water flow.

- Surface and Ground Water Protection: Wetlands often store and infiltrate rainwater to the underlying groundwater system.

- Erosion Control: Wetlands store and infiltrate water, reducing runoff and flooding hazards downstream, helping to prevent erosion.

- Pollution Treatment and Nutrient Cycling: Wetlands improve water quality by absorbing pollutants, reducing turbidity,5 and breaking down and recycling organic materials back into the environment.6

- Fish and Wildlife Habitat: Wetlands are one of the most productive habitats for feeding, nesting, spawning, resting, and cover for fish and wildlife, including many rare and biodiversity.

- Public Enjoyment: Wetlands provide areas for recreation, education, and research. They also provide valuable open space, especially in developed areas, where they are some of the only green space remaining.8

History of Wetlands in the U.S.

Before the 1970s, wetlands were mostly considered problem areas basically because they were too wet too develop. Thus, sadly they became a trash dumping grounds. Mary Ann Cunningham, a geography professor at Vassar College, said in a recent interview; “it was pretty typical to throw junk in a wetland.” Professor Cunningham showed students aerial photographs from the year 1936 of New York State’s Casperkill watershed (a wooded wetland), pointing out how the FICA and Brickyard Hill landfills were both initiated wooded wetland. Unfortunately, the FICA landfill filled in the wetland to such a great extent that it displaced the local streams by 20 meters.9

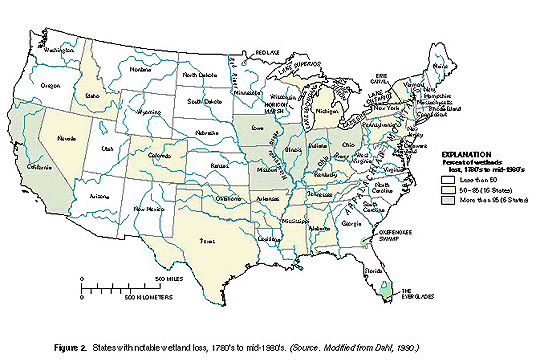

In fact, in the 1960s there were a number of political and even financial incentives to drain and destroy wetlands. The federal government subsidized a number of wetland draining projects for “storm control” and to increase agricultural land area. According to one U.S. Geological Survey paper, the Agriculture Conservation Program’s policies caused wetland losses averaging a whopping 550,000 acres each year from the mid-1950s through the mid-1970s. Agricultural practices in the U.S. were responsible for at least 80% of those wetland losses.10

11

11

Wetland Protection Efforts

It wasn’t until very recently that people began to recognize that wetlands are valuable areas with important environmental functions. The first way in which the federal government started to preserve wetlands was through acquisition. The Fish and Wildlife Service estimates that 12.5 million acres of wetlands in the contiguous U.S. are owned and leased by the Federal government. Although acquisition will certainly remain an important part of the Federal wetland conservation strategy, with most of the remaining wetlands in private hands, it is simply too expensive to expect fee-based acquisition and easement programs to be the main wetland conservation strategy.12

Section 404 of the Clean Water Act is the only Federal program that directly regulates wetland use. Section 404 requires that before anyone discharge dredge or fill material into a wetland, they obtain a permit from the Corps of Engineers. Unfortunately, this program does not place restrictions on other activities that might alter a wetland, such as excavation, drainage, clearing, flooding, or degradation due to chemical runoff. In addition, enforcement of Section 404 is often lax.13

Section 402 of the Clean Water Act also protects wetlands, albeit less directly, by regulating what “point sources” discharge into a watershed. In 1987, amendments to Section 402 addressed runoff from non-point sources (e.g. stormwater runoff from agricultural, forestry, and urban areas) by directing States to develop and implement non-point pollution management programs.14

Many states such as New York and California have local regulations, most of which are similar to the 1975 New York State Freshwater Wetlands Act (NYFWA). The NYFWA commits state officials to “preserving, protecting and conserving freshwater wetlands and their benefits, consistent with the general welfare and beneficial economic, social and agricultural development of the state.” The act protects wetlands larger than 12.4 acres, although smaller wetlands can be protected if they are considered of unusual importance.15 The following section of the act (Title 7 §24-0701) explains which activities are regulated:

Activities subject to regulation shall include any form of draining, dredging, excavation, removal of soil, mud, sand, shells, gravel or other aggregate from any freshwater wetland, either directly or indirectly; and any form of dumping, filling, or depositing rubbish or fill of any kind, either directly or indirectly … These activities are subject to regulation whether or not they occur upon the wetland itself, if they impinge upon or otherwise substantially effect the wetlands and are located not more than one hundred feet from the boundary of such wetland.16

Unfortunately, 12.4 acres is a rather large area of land. There is still opportunity to protect smaller wetlands and for additional States to enact legislation protecting wetlands. This is especially so when considering that as of 2008 only 23 States have legislation in place that requires permits for dredge and fill activities in wetlands and other waters. These are mainly coastal States and notably North Dakota.17 Let’s hope that in the very near future we see all States enacting legislation to protect their wetlands and other waters. For a highly detailed discussion of State wetland protection, read this study by the Environmental Law Institute.